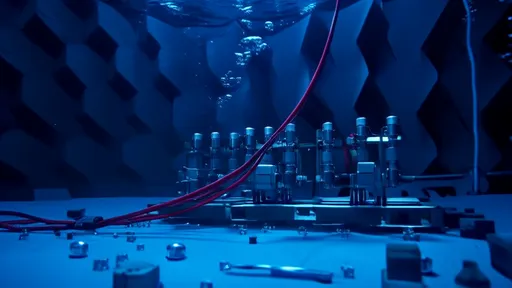

The mysteries of sound propagation beneath the ocean's surface have long fascinated scientists and engineers alike. Underwater acoustic attenuation models represent a crucial field of study that bridges theoretical physics with practical applications ranging from marine navigation to submarine communications. These sophisticated mathematical frameworks attempt to quantify how sound waves lose energy as they travel through the complex medium of seawater.

Understanding the fundamental physics behind underwater sound attenuation requires grappling with several interacting phenomena. Unlike in air, where sound attenuation follows relatively straightforward principles, the aquatic environment introduces frequency-dependent absorption, scattering effects, and complex boundary interactions. The viscosity of water, its temperature gradients, and even dissolved salts all play significant roles in shaping how sound diminishes over distance.

The development of accurate attenuation models traces back to World War II, when naval operations urgently needed reliable methods for predicting sonar performance. Early pioneers like Leonhard Liebermann recognized that classical acoustics theories developed for airborne sound failed to account for the unique molecular relaxation processes occurring in seawater. This historical context underscores how military applications have often driven fundamental research in this field.

Modern attenuation models incorporate multiple physical mechanisms operating simultaneously. Chemical absorption, where sound energy gets converted into heat through molecular vibration, typically dominates at higher frequencies. Below 10 kHz, viscous absorption caused by shear forces in the water becomes increasingly important. The presence of magnesium sulfate and boric acid in seawater creates additional frequency-dependent absorption peaks that no model can afford to ignore.

Temperature and pressure gradients in the ocean add further complexity to sound propagation. The so-called "deep sound channel" at certain depth ranges can guide sound waves with remarkably low attenuation over hundreds of kilometers. Conversely, shallow coastal waters often exhibit highly variable attenuation characteristics due to turbulent mixing and suspended sediments. These environmental factors challenge modelers to develop adaptable frameworks rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

Practical applications of these models extend far beyond theoretical interest. Marine geophysicists use attenuation corrections when interpreting seismic survey data for oil and gas exploration. Naval architects incorporate attenuation predictions when designing ship sonar systems. Even marine biologists benefit from understanding how different frequencies attenuate, as this affects how far whale songs or other biological sounds can travel through the oceans.

The evolution of computational power has transformed attenuation modeling from a purely theoretical exercise into a tool for real-world problem solving. Modern implementations often combine physical principles with empirical data through machine learning techniques. This hybrid approach allows models to maintain scientific rigor while adapting to the messy realities of actual ocean conditions that rarely match textbook examples.

Climate change research has recently emerged as an unexpected beneficiary of advances in acoustic attenuation modeling. As ocean temperatures and acidity levels change, so too do the medium's acoustic properties. Carefully calibrated attenuation models now help scientists detect subtle changes in seawater chemistry by analyzing how measured sound propagation differs from predicted values. This application demonstrates how a field originally developed for military purposes now contributes to environmental monitoring.

Commercial interests continue driving innovation in attenuation modeling as well. The offshore wind industry requires precise acoustic environmental impact assessments for turbine installations. Underwater data centers being developed by major tech companies need to account for acoustic interference in their cooling systems. Each new application pushes modelers to refine their approaches and consider previously neglected factors.

The future of underwater acoustic attenuation modeling likely lies in increased integration with other oceanographic disciplines. Combining traditional physics-based models with real-time sensor data from autonomous underwater vehicles could create dynamic, self-correcting systems. Some researchers envision "digital twin" representations of ocean basins that continuously update their acoustic properties based on multiple data streams.

As with any scientific modeling endeavor, challenges remain in balancing complexity with practicality. The most sophisticated attenuation models risk becoming computationally prohibitive for field applications, while oversimplified versions may miss critical phenomena. This tension ensures the field will continue evolving as computing capabilities advance and our understanding of ocean physics deepens.

What began as a specialized tool for sonar engineers has grown into a multidisciplinary science touching nearly every aspect of underwater acoustics. From protecting marine mammals to securing underwater communications, modern society increasingly relies on accurate predictions of how sound behaves beneath the waves. The quiet revolution in attenuation modeling continues to make these applications possible.

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025